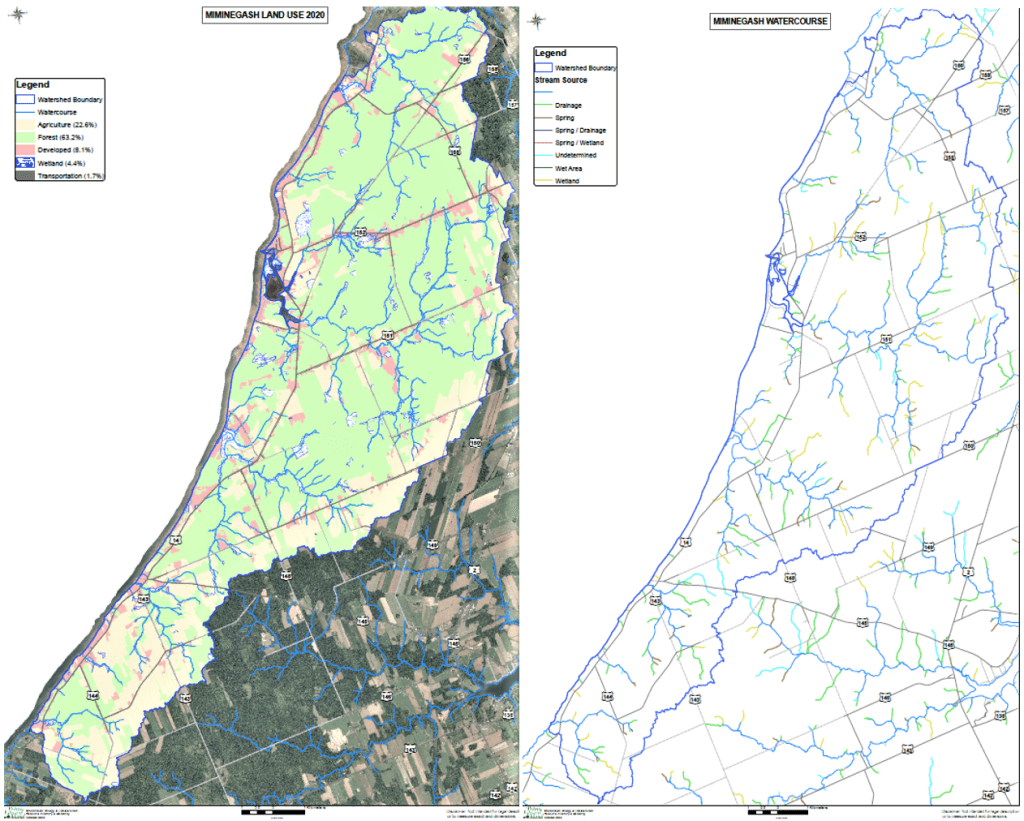

The Miminegash River Watershed encompasses a large fourth order river system. It has a 6,020-hectare drainage system that is made up of 69% forest cover, 20% agriculture, 5% wetland, and 5% development. The headwaters of this system originate in communities such as St. Louis, St. Edwards, St. Lawrence, Loretta, Brockton, and Elmsdale. There are three main stream branches which made up the entirety of the watershed, both of which flow to Miminegash Pond and then to Miminegash Harbour before outletting into the Northumberland Straight. Along the entirety of this river system is a rich history stretching back for thousands of years.

Indigenous people living on the land now known as Prince Edward Island are the Mi’kmaq, who have lived in their traditional territory of Mi’kma’ki. They are the only people native to PEI. The Mi’kmaq originally named PEI as “Epekwitk” meaning “lying in the water”. The Mi’kmaq lived in an annual cycle of seasonal movement between living in dispersed interior winter camps and larger coastal communities during the summer. The Mi’kmaq name “Elminikej” means “Let us carry something animate on our shoulders (Portage)” and is the traditional Mi’kmaq name for the Miminegash River.

The Miminegash River Watershed was stewarded by the Mi’kmaq as far back as 12,000 years ago. Wild Atlantic salmon (plamu’l ) and American eel (K’at), from the Miminegash river (Elminikej) are an important resource. Prior to European colonization, Mi’kmaq perched in Miminegash River Watershed during the warner months and migrated into the woods in the colder months. It was the Mi’kmaq who started the local fishery.

From the 1860s to the 1920s, Miminegash contained many thriving lumber mills to support ship building and more. The historic “Green’s Mills,” lumber mill was located above Route 14 bridge in St. Lawrence PEI, also commonly known as “Green’s Bridge,” and a second mill was located on Center Line Road near Roach’s Bridge, upstream of “Community Pastures.” Both were operated by the Green family and lumber was sourced locally and cut for local needs such as their personal furniture business and a ship building company operating downstream of Miminegash River. The mills also provided a supply of lumber to build the Miminegash Methodist church in 1880.

The mill was described as a substantial operation, with a large water wheel and flooded upstream pond. The frozen floodplain was used as a lumber yard in winter. The pond was back flooded in the evening after the mill closed for the day, so that by morning the extra water would pressurize the water wheel and lumber could be cut faster during daylight hours. Horse and sleigh or wagon hauled lumber to and from the mills.

Ship building between 1860-1920s was done within the Miminegash River estuary and lumber was sourced locally from the Green family mill to supply the operation. Schooners were built, filled with lumber, and then sailed to other regions to sell their cargo. Several schooners were built in Miminegash and sold regionally. The shipbuilding company employed the Green family, Constain family, and Rix family amongst others in the community.

Winter horse racing was popularized from 1900-1940s. Horse and sleigh races occurred each Sunday on the Miminegash Pond below Green’s Bridge, weather and ice conditions permitting. People from as far as Alberton and surrounding areas frequently attended, and occasionally people from eastern PEI arrived on the train to St. Louis with their horses on the train to compete. They would race for prizes, bragging rights, and to keep their horses in shape for summer races (harness racing).

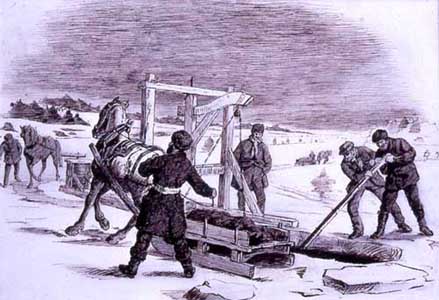

The establishment of a mussel mud business also coincided with the period between 1900 to 1940 and certain community members had devices that collected mussel mud. A mussel mud harvester would sit atop a 6-ft wide hole in the ice of the Miminegash River estuary, with a bucket 18-24 inches deep. Much like a trawling grapple, it sat on the seabed and dredged up the mud under the ice. It was linked to a harness pulled by horse, where block and tackle were above the ice, and the mussel mud would be deposited into sleigh with racks to be sold by the bucket or the yard, stockpiled close to the field, and then spread over fields as agricultural fertilizer. Some areas were dug four meters deep, and a hole remains where those areas were harvested over one hundred years, now infilled with fresh sediment and perfect habitat for American eel.

The eel net fishery became popularized in the late 1960s to present, where eels are caught in eel nets alive. An eel spear was a device used for pronging eel in the mud. Once one caught an eel, the device would wriggle to indicate a catch. In the winter, the spear was the size of the hole that had been cut into the ice, with multiple spears on the end of a pole, like a fork. Rainbow smelt seine fishing in Miminegash Pond was popularized by the Constain family, who shipped smelt by train to buyers down east. The pond also hosts migrating waterfowl, at greater populations in the past compared to present, with wild geese and ducks roosting every evening.

A Brook trout nursery was established from 1996-2001 within a groundwater spring off the center line road above Roach’s bridge. As it grew, silt became an issue that began to impact the survival of the trout, so it was moved. From 2001-2006 the nursery produced Brook trout out of Carr’s Brook tributary. It was supported by PEI Forest, Fish and Wildlife Division, and in 1995/96, biologists successfully identified a single female Brook trout and six small males during electrofishing surveys. At the time, the habitat in Miminegash River was highly impacted by beaver dam activity and siltation that was suggested to have caused decreases in fish populations. At the hatchery, Miminegash River’s female Brook trout eggs reproduced with milt of male Brook trout from Trout River Watershed (Mill River). The result was 2,500 fertilized eggs to be returned to the Miminegash River nursery. The original Miminegash River Brook trout were reported to have behaved in such a way as to suggest that they never habituated to pond conditions, but as their genetics changed from introducing new populations into the area, they began to display signs of habituating the pond. After the second year of stocking, populations increased; nursery hatched Brook trout were being caught in the pond and at the narrows of Miminegash River by the third year of the initiative.

In spring of 1987, Peter Murphy was granted funding and permitted to raise 1,500-2,000 Rainbow trout (fry and parr), and nurse them in a stream side pen below the Green’s bridge on Route 14 in St. Lawrence, on the Miminegash River. Drought conditions persisted in August that resulted in 80% die-off and only 20% were released. Biologist at the time made a visual assessment that the fish were oxygen deprived. Sample collection and lab analysis indicated that parasites were also a possible cause of the large population death.

In the late 1960s, the Miminegash River was lined with elm, cedar and ash and the stream bottom was composed of a mixture of gravel and cobble. It was not unusual to catch wild Atlantic salmon parr when fly fishing for Brook trout, as per accounts by prominent local biologist Daryl Guignion. In the years since, wild Atlantic salmon populations waned and none were successfully identified during electrofishing surveys in 2001-2002, conducted as part of intensive graduate research in several PEI streams (Guignion et al., 2010). In 2018, several Atlantic salmon parr were being angled in the Miminegash River, and it was added to the list of rivers being surveyed in late autumn. It did not take long to verify that Atlantic salmon had indeed returned, and Miminegash River is now the only south-draining river in West Prince to have Atlantic salmon according to the Renewed Conservation Strategy for Atlantic Salmon in Prince Edward Island (locally referred to as the Guignion Report) published in 2019, containing survey data and recommendations by provincial experts.